What are the ingredients of that delicious pizza?

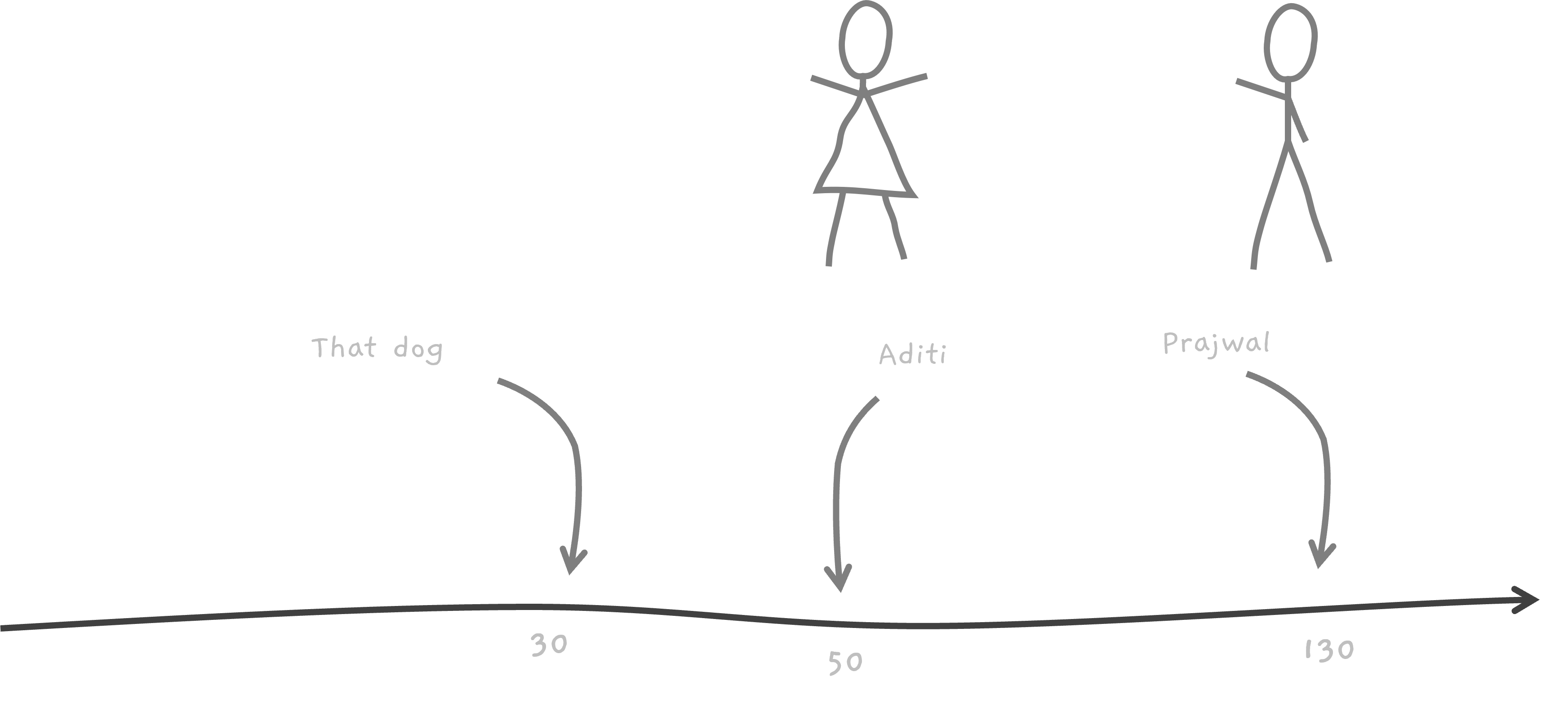

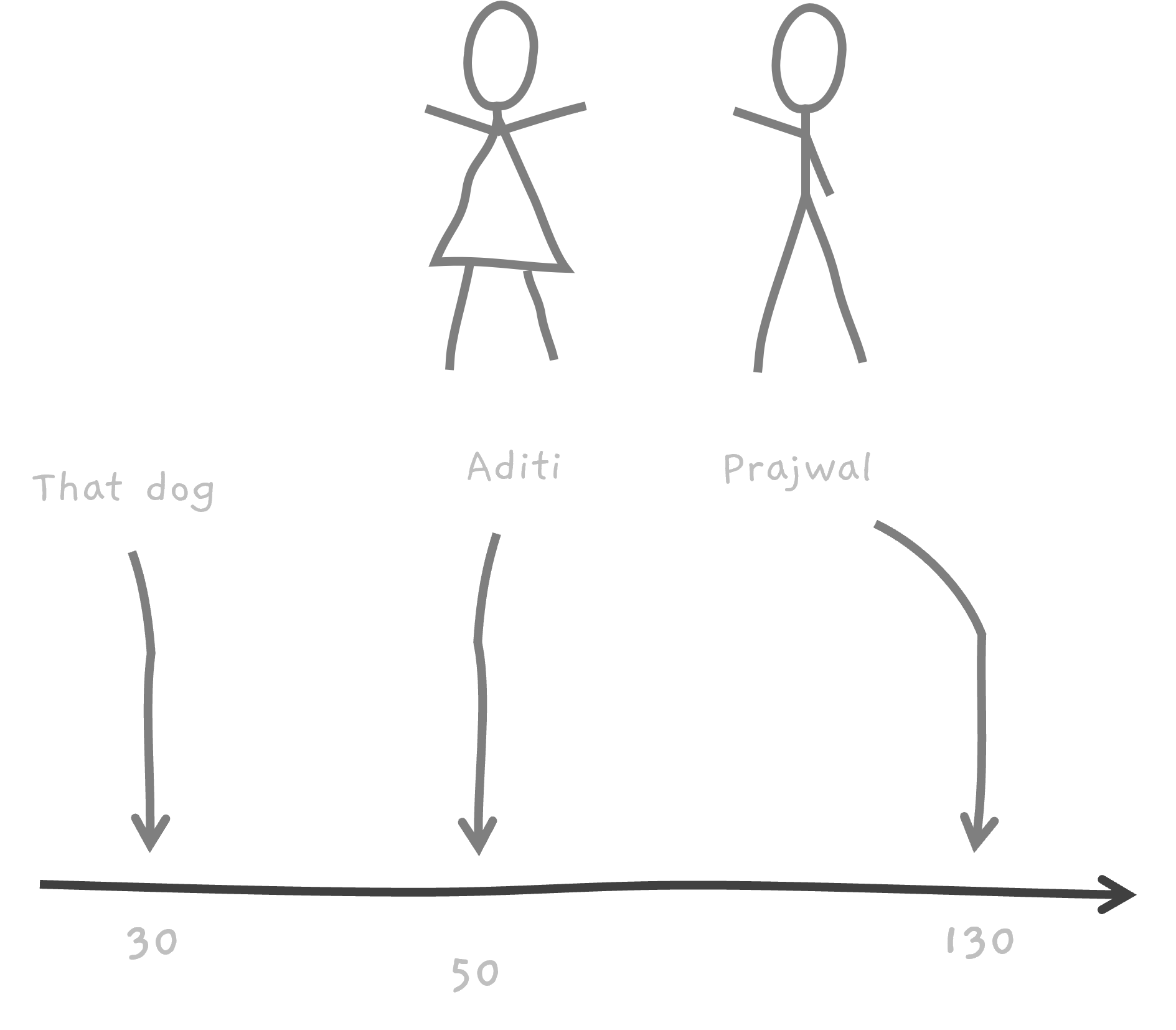

Aditi Sharrma, Prajwal DSouza

Proteins, the mighty microscopic marvels present in what we eat, hence, what we are. In milkshakes 🥤, ice creams 🍦... your hair, your skin… you 👤. These molecular machines are present in all living things, from viruses to the dog 🐶 that barked at you the other day. They are so essential that they keep the grand show of life going. Proteins are like the ultimate multi-taskers of the cellular world. They're the tiny construction workers 🏗️, dutiful soldiers, speedy messengers, vigilant guards and the skilled repair crew 🔧 that keep our bodies running smoothly day in, day out.

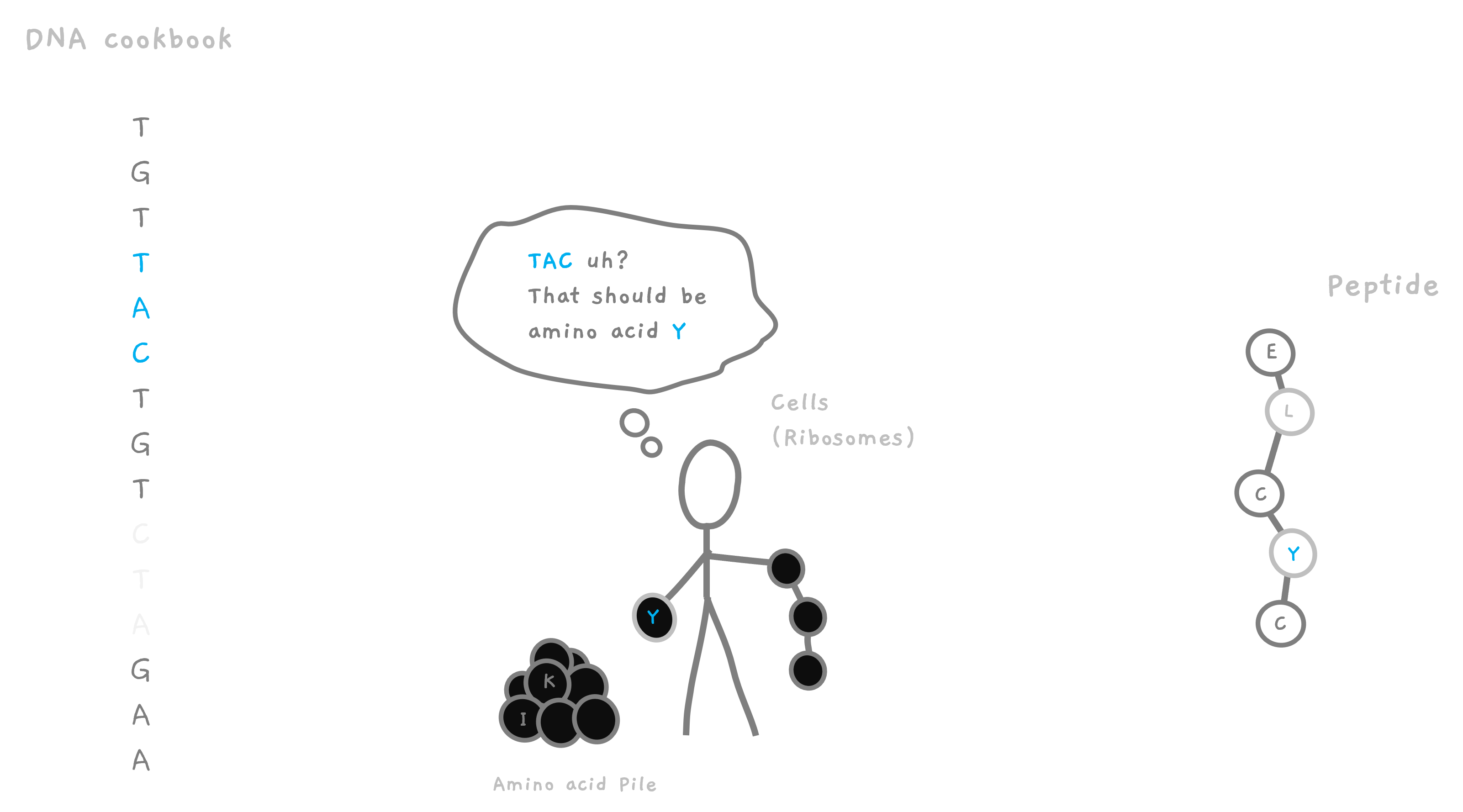

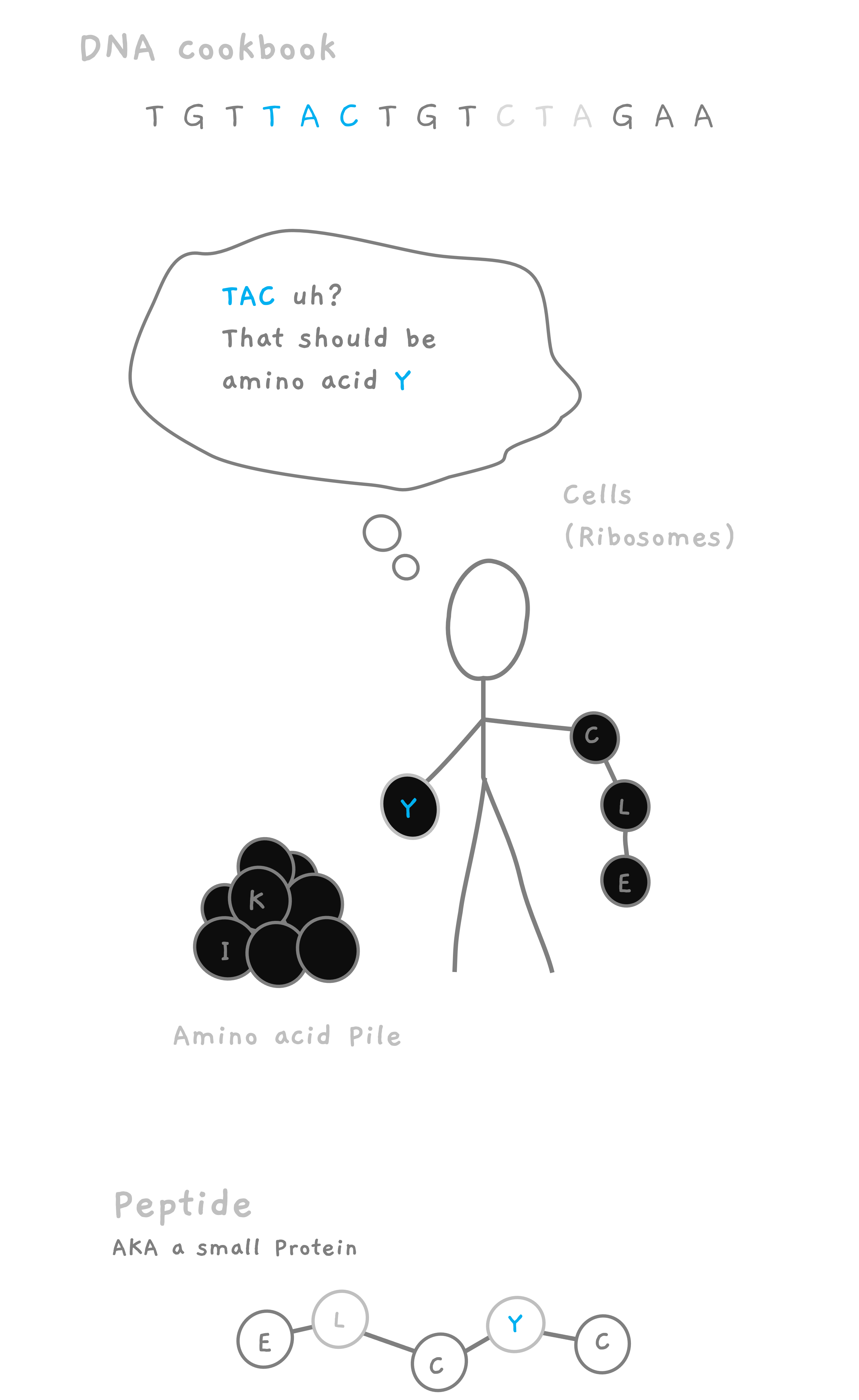

They're crafted by our cells using the blueprints written in our DNA. Heard of the genetic code in the DNA? This code is like a huge library 📚, stuffed with cookbooks. These cookbooks contain genes, which are like recipes for whipping up every protein your body needs. And there are at least 10000 different proteins keeping you alive.

These proteins are built inside your cells using tiny molecules called amino acids 🧪, which are like the ingredients in your recipe. These cells are guided by the instructions in the DNA on how to put together particular proteins. Picture a cake 🍰, it needs flour, eggs, sugar, and butter, all in specific quantities and added in a certain order. Similarly, proteins need specific amino acids in the right order to be cooked up right. DNA has the recipe, cookbooks 📚. Amino acids are the ingredients. Proteins are the dishes 🍽️. Hungry yet? 😋

As an example, the following genetic code in your DNA, could be the cookbook instruction 📖 for creating the dish (protein) we want.

TGT - TAC - ATT - CAA - AAT - TGT - CCT - CTC - GGT

These instructions would lead the cells to place amino acids (ingredients) one after another leading to a molecular chain of amino acids placed in the following order.

Cysteine - Tyrosine - Isoleucine - Glutamine - Asparagine - Cysteine - Proline - Leucine - Glycine

CYIQNCPLG

In this case, the instruction earlier in the DNA was for a small protein (technically peptide, but we will get to that.) called Oxytocin 😍, often referred to as the "love hormone" or the "cuddle chemical." It plays a crucial role in social bonding, fostering feelings of trust, empathy, and connection. The amino acid sequence for this oxytocin is CYIQNCPLG.

There are over 20 amino acids, and only using 20 of these, our bodies create 10,000 different types of proteins, with each protein playing a different role. For example, hemoglobin protein 💉 is made by the cells in your bone marrow, because the cells are instructed by your DNA to do so, which is then released into your bloodstream. Tyrosinase is another protein, which is responsible for producing melanin, which gives your hair the color 🌈. Loss of this protein, or cells choosing not to produce it can lead to loss of hair color.

While oxytocin is just 9 amino acids, hemoglobin is about 300 and Tyrosinase is over 500 amino acids long.

So, What is de novo sequencing?

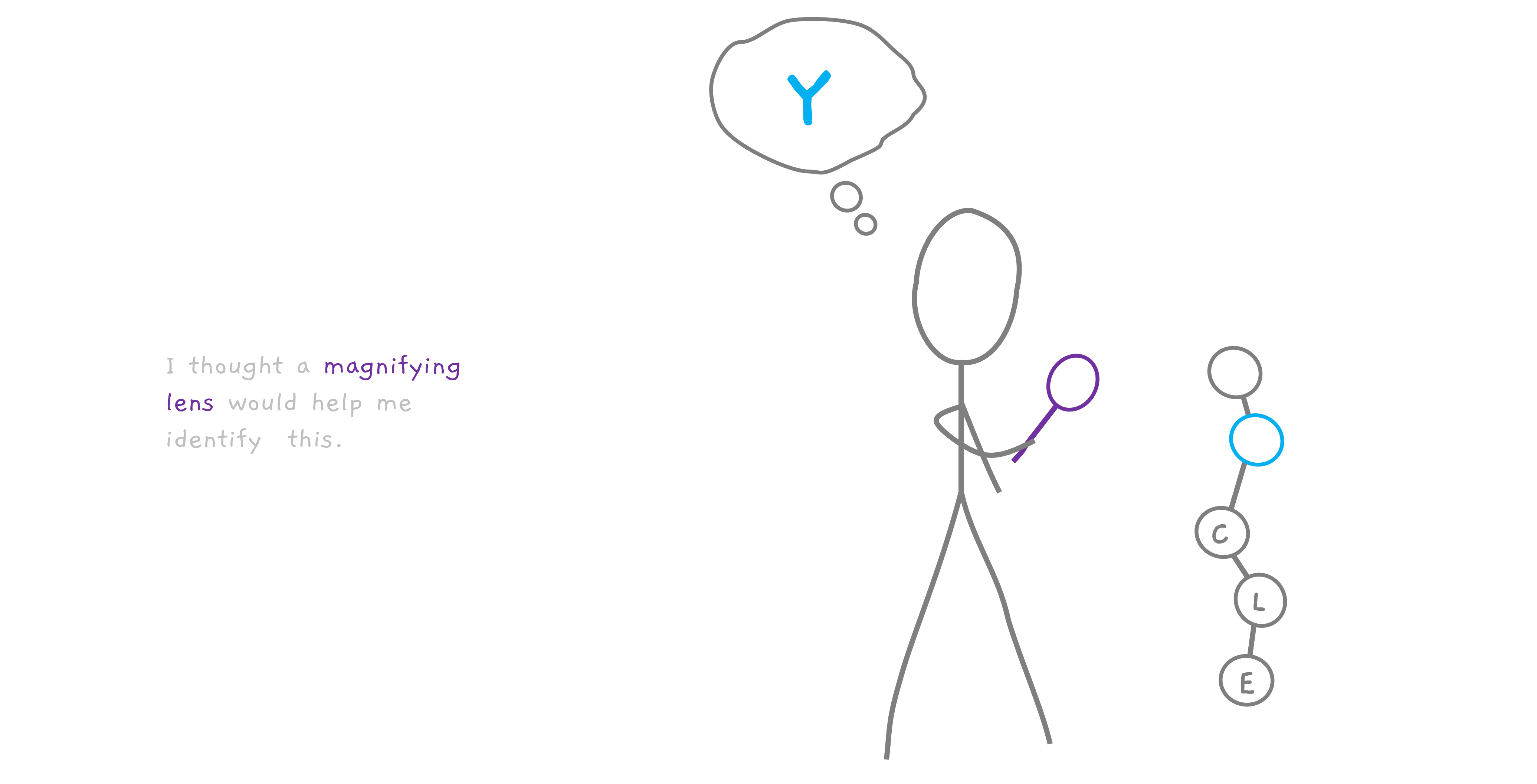

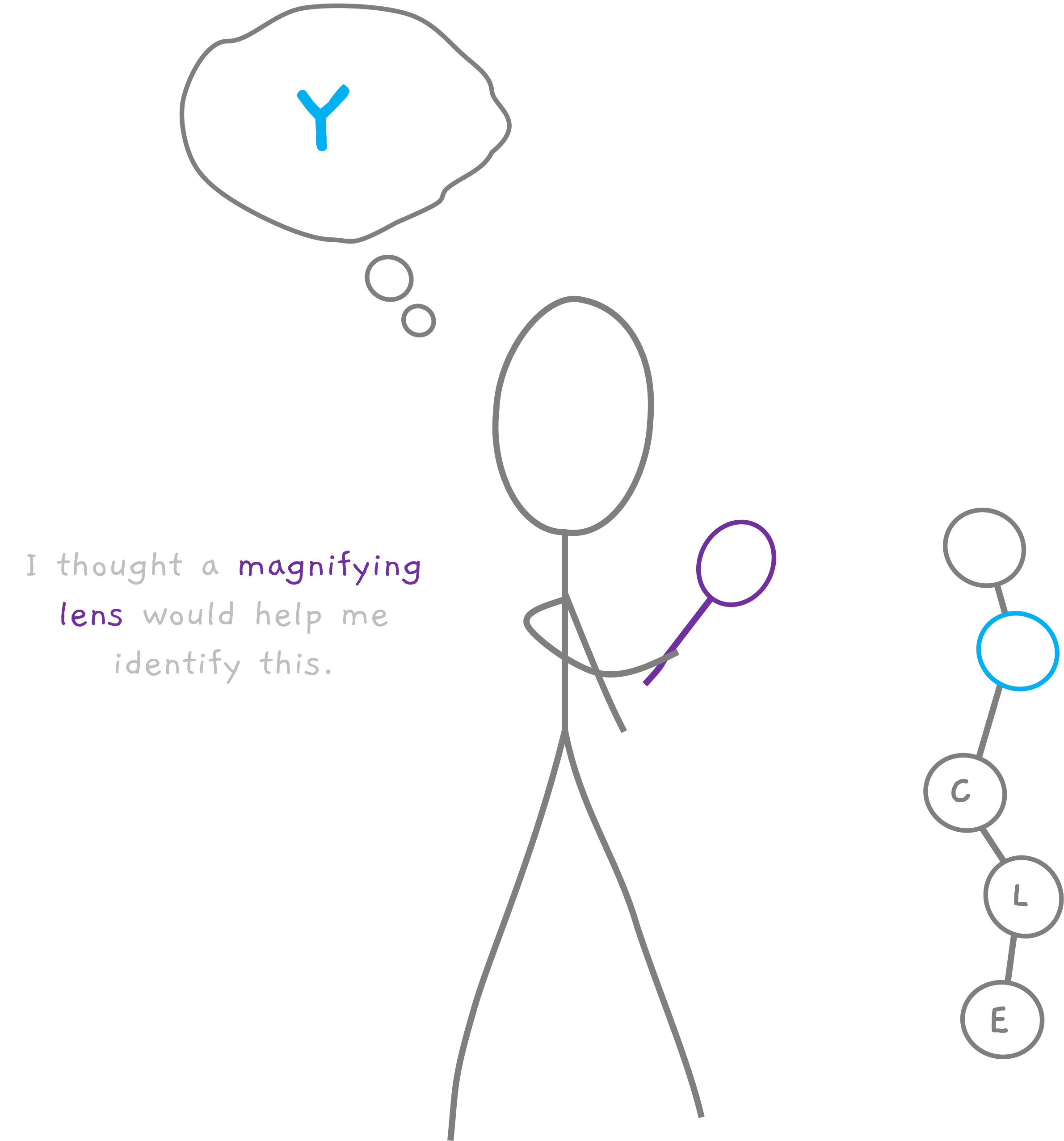

Here's the big challenge. Let's call it "de novo sequencing" which is a fancy way of saying "figuring out the ingredients of a protein by tasting it" 🕵️♀️🔍. It's like heading to a restaurant, eating a lip-smacking dish 🍲, and then trying to identify the ingredients just based on your taste! Sounds fun but tough, doesn't it? The goal is to identify the composition and sequence of the protein. That is, to identify the amino acid pattern.

At this point, allow me to introduce the superstars of our story — peptides. Peptides are like mini proteins. Think about a giant pizza 🍕(that's your protein), peptides are like those cute mini pizza bites, smaller in size but oh-so-crucial. Peptides are just shorter chains of these all-important amino acids. Remember oxytocin, that's a peptide, a mini protein. 💖

From now on, we're shining the spotlight 🎯 on these little strands of amino acids, the peptides. Let's think of them as the underdogs, small but mighty, and loaded with info about our bodies. 🏋️♀️

So, why the heck do we want to figure out the sequence of the peptide? 🤷♀️ Well, if we crack the sequence of amino acids - the 'secret ingredients' 🧪 - in our peptide, we unlock a whole treasure chest 🗝️🔓 of information about what it is and what it does. It's like decoding a secret message written in an alien language! 👽📜

By identifying a peptide in a sample, we could potentially develop a new wonder drug 💊 that uses the peptide, or a treatment that blocks it. It's like having a secret weapon in the battle against diseases! 🛡️ We could even learn something groundbreaking about how the body works! 🧠⚡ It's like discovering a new law of physics... but inside our bodies! How cool is that? 🤓🚀

So, how do we do it?

Well, we could just squint really hard at them under a microscope 🦠🔬. But trust me, even if you have the eyes of an eagle, you wouldn't see much. They're way too small. Sure, there have been some incredible advances recently with techniques that read each amino acid, but it's still not always possible.

How about just weighing it? 🏋️♀️ If my peptide weighs, let's say, 200 (in super-simplified units), then I could whip out a catalog 📚 and see that 200 is the mass of oxytocin. So, it must be oxytocin, right? Ehhh... not so fast. There could be a whole bunch of other peptides out there that also weigh 200. Worse, what if this peptide is from a snake venom 🐍 that's never been observed before and hence, doesn't even make it to the catalog?

Aha! Scientists early on had a light bulb 💡 moment. They thought, "Let's break the peptide into pieces, then weigh the pieces." It's like disassembling a Lego tower to understand how it was built.

But then, a new challenge raises its ugly head 🐲. How do we weigh so many tiny pieces at once? It's like trying to weigh a bunch of confetti 🎉 - all at the same time!

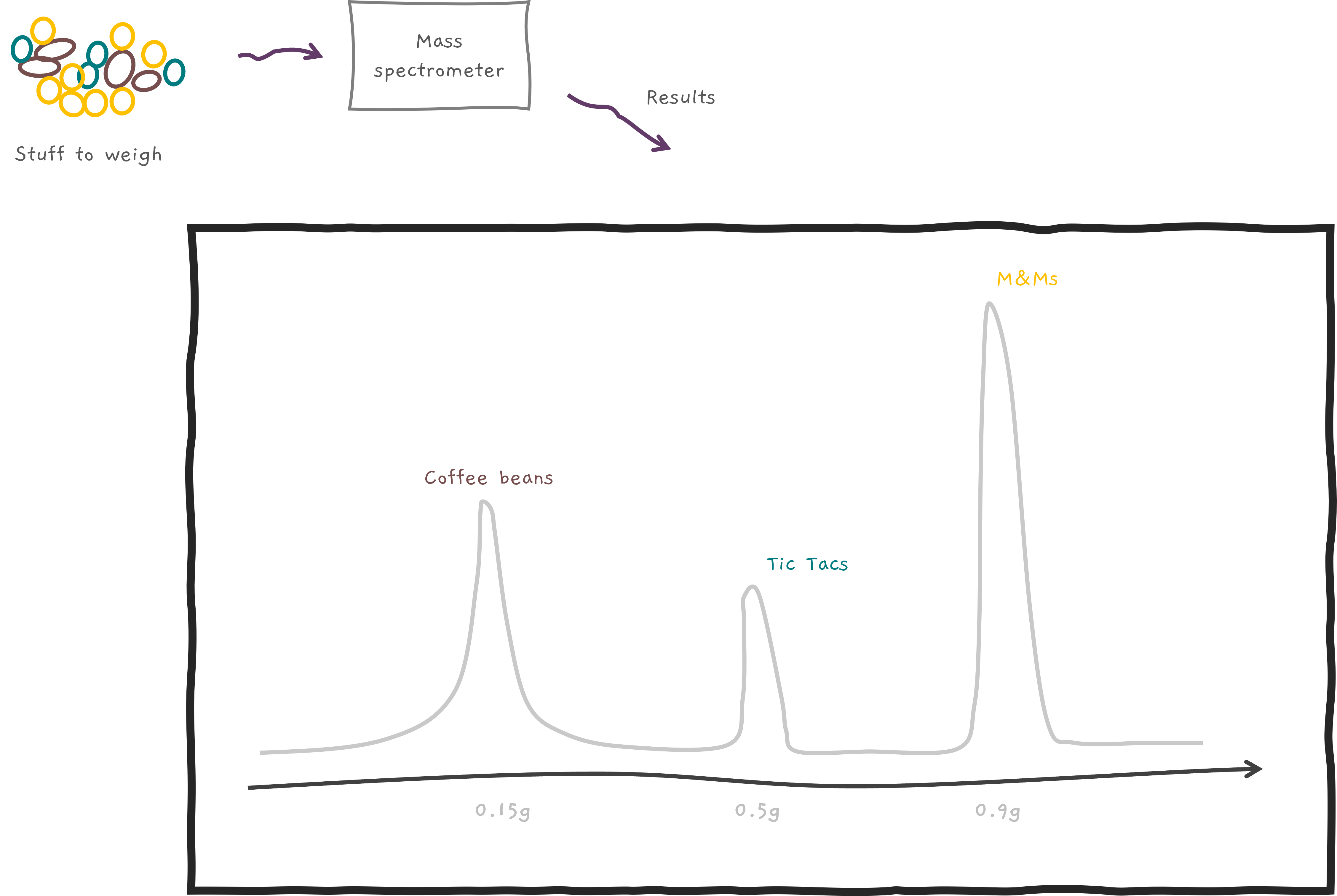

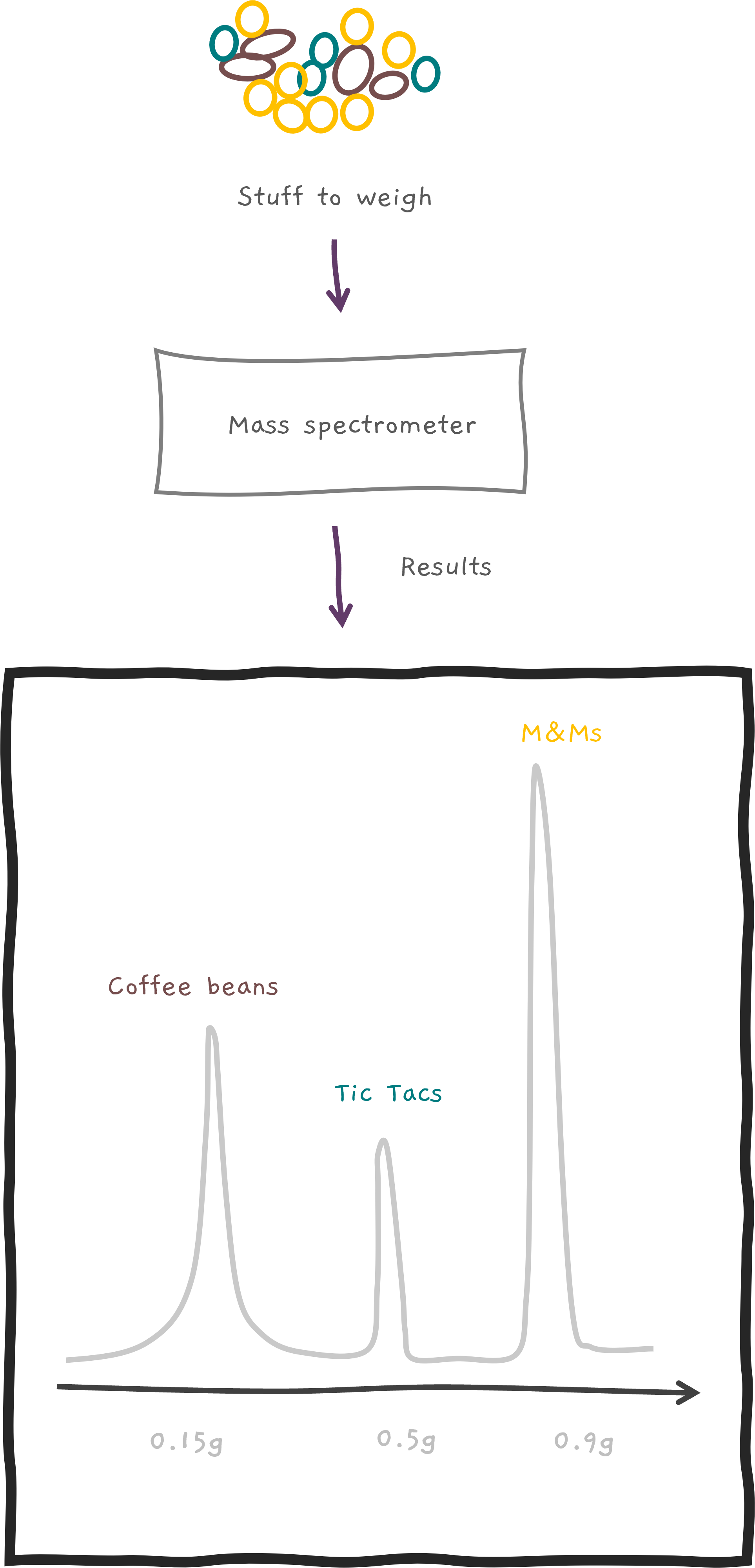

Enter the unsung heroes of our story - mass spectrometers 🌠. These are like high-tech super scales 🧱⚖️ that can weigh a ton of things all at once.

But wait, there's more! We usually measure a lot of things at once, and mass spectrometers don't just stop at weighing. They also measure quantities 🔢. It's like a super-smart scale saying... "Oh, your sample had more M&Ms 🍫 than Coffee beans ☕ in your Mocha coffee bean cookie 🍪." How cool is that!?

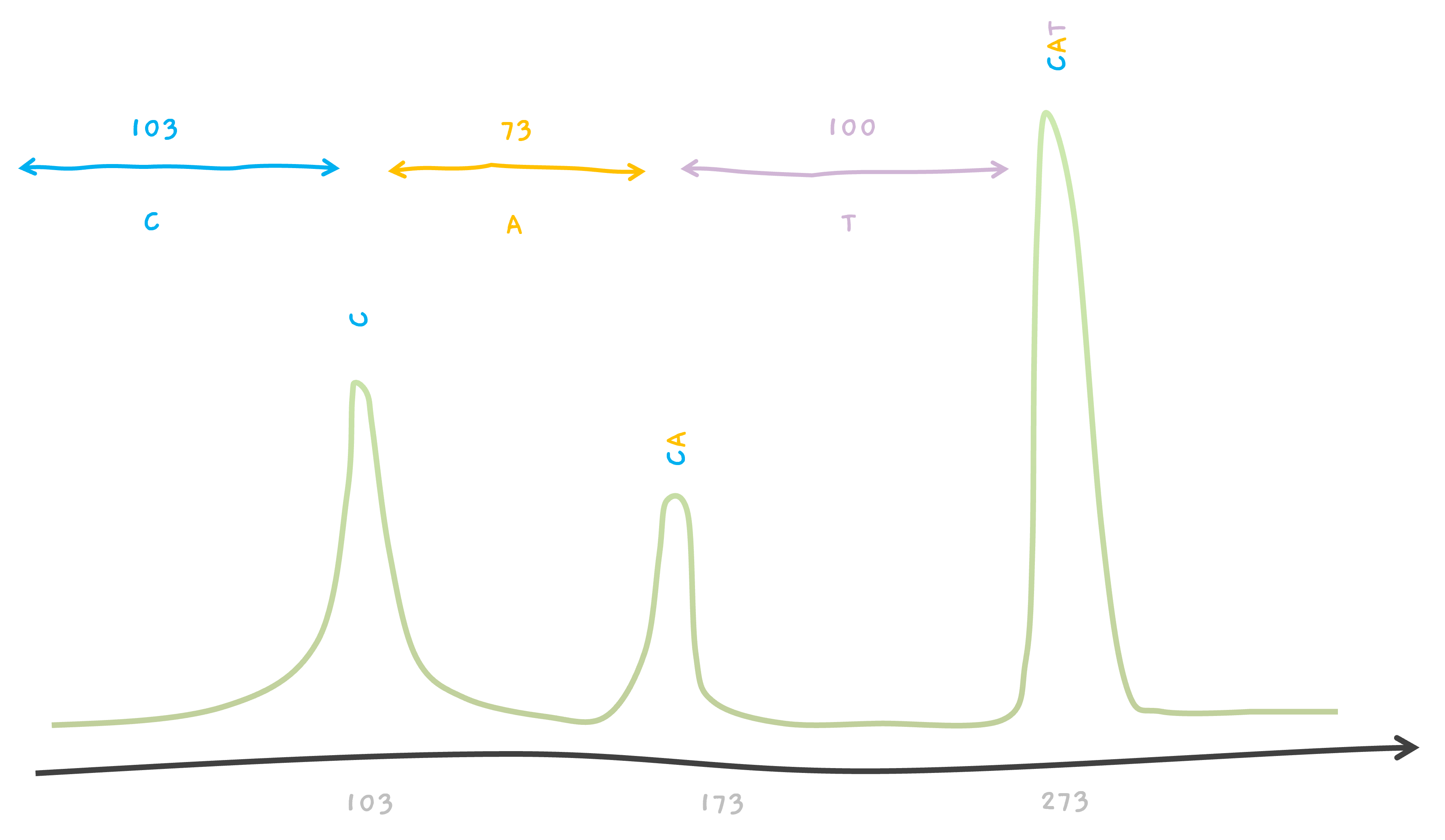

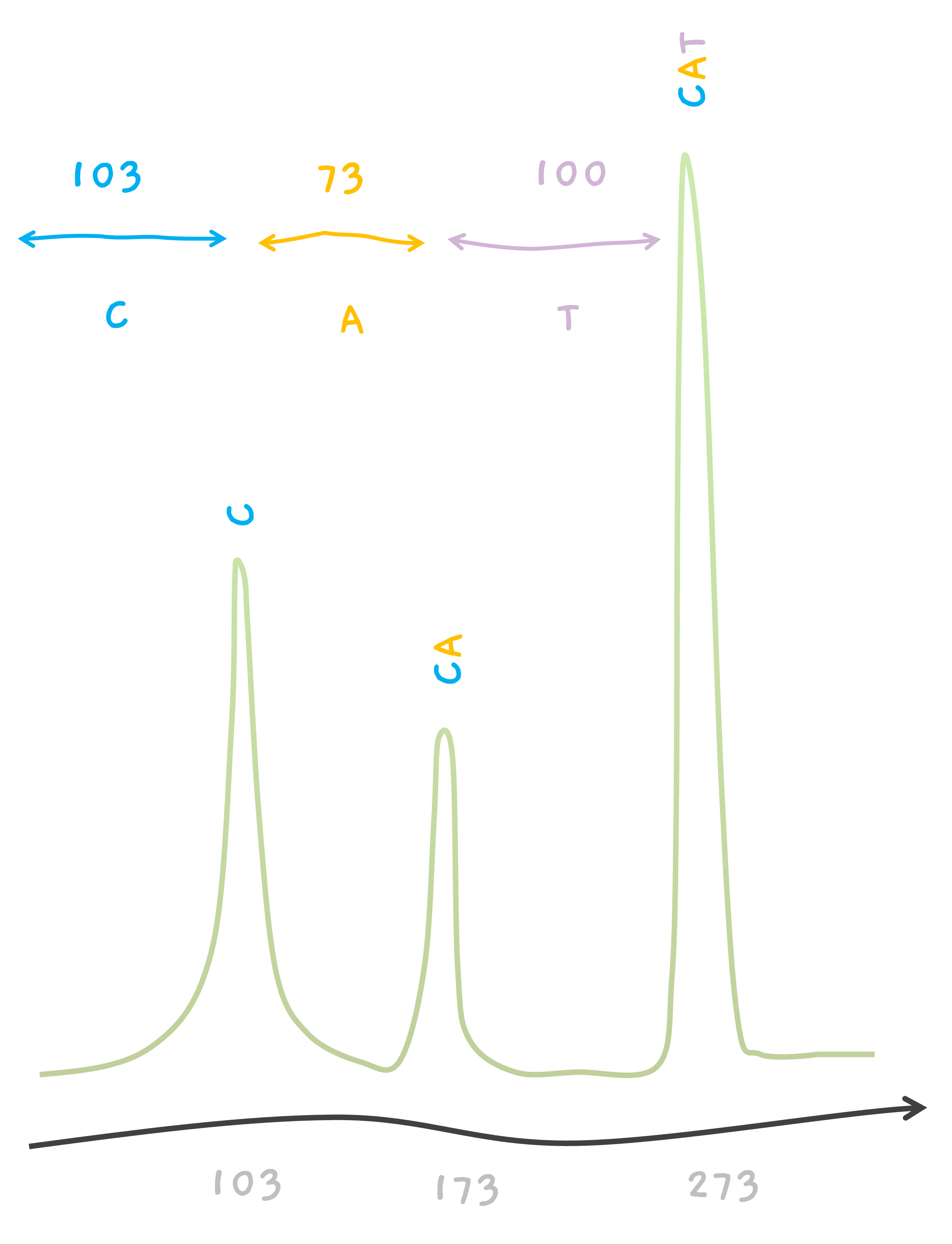

Let's say we've got our hands on a peptide called CAT (not the furry creature 🐱 but a peptide whose amino acid sequence is C, A, and then T). In fact, let's say we have a whole pile of them, like a giant CAT party 🎉. But before we can start the weighing party, we've got to break them into smaller parts. Kind of like smashing a piñata 🎊. And we have some pretty fancy ways to do this (imagine sophisticated scientific pinata smashers like CID, ETD etc.).

When we bash our CAT peptide, it can break into C, CA pieces.

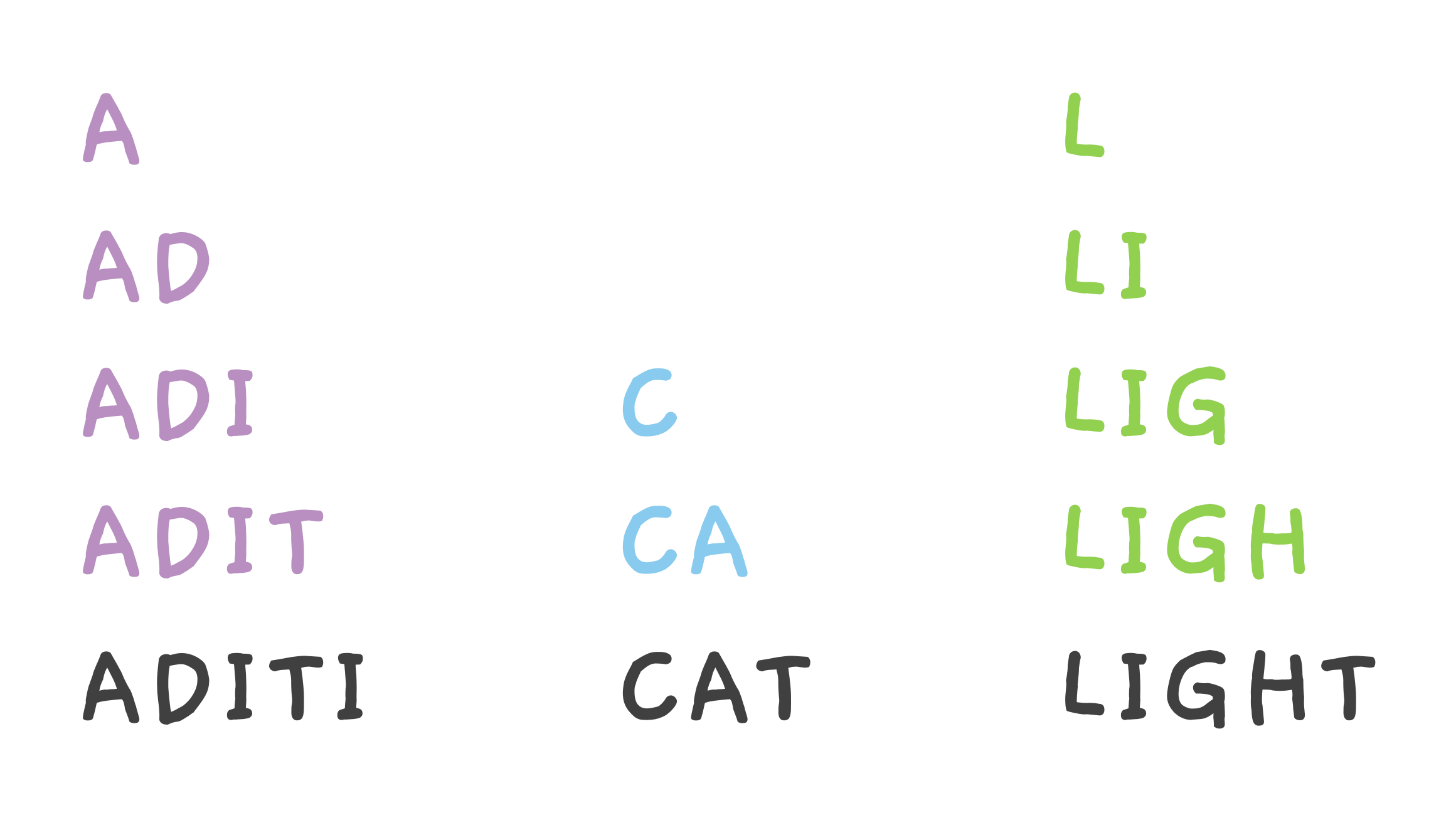

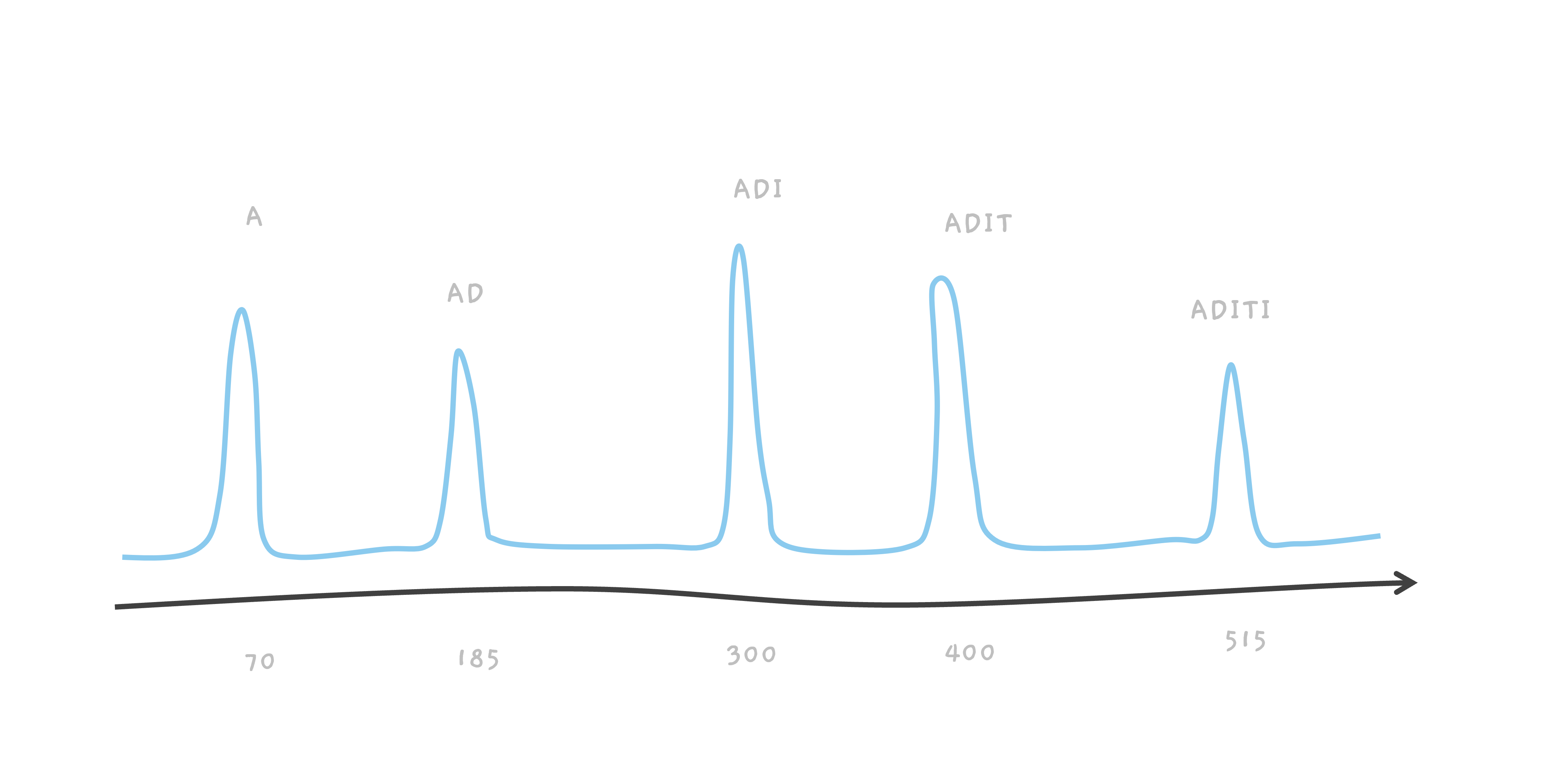

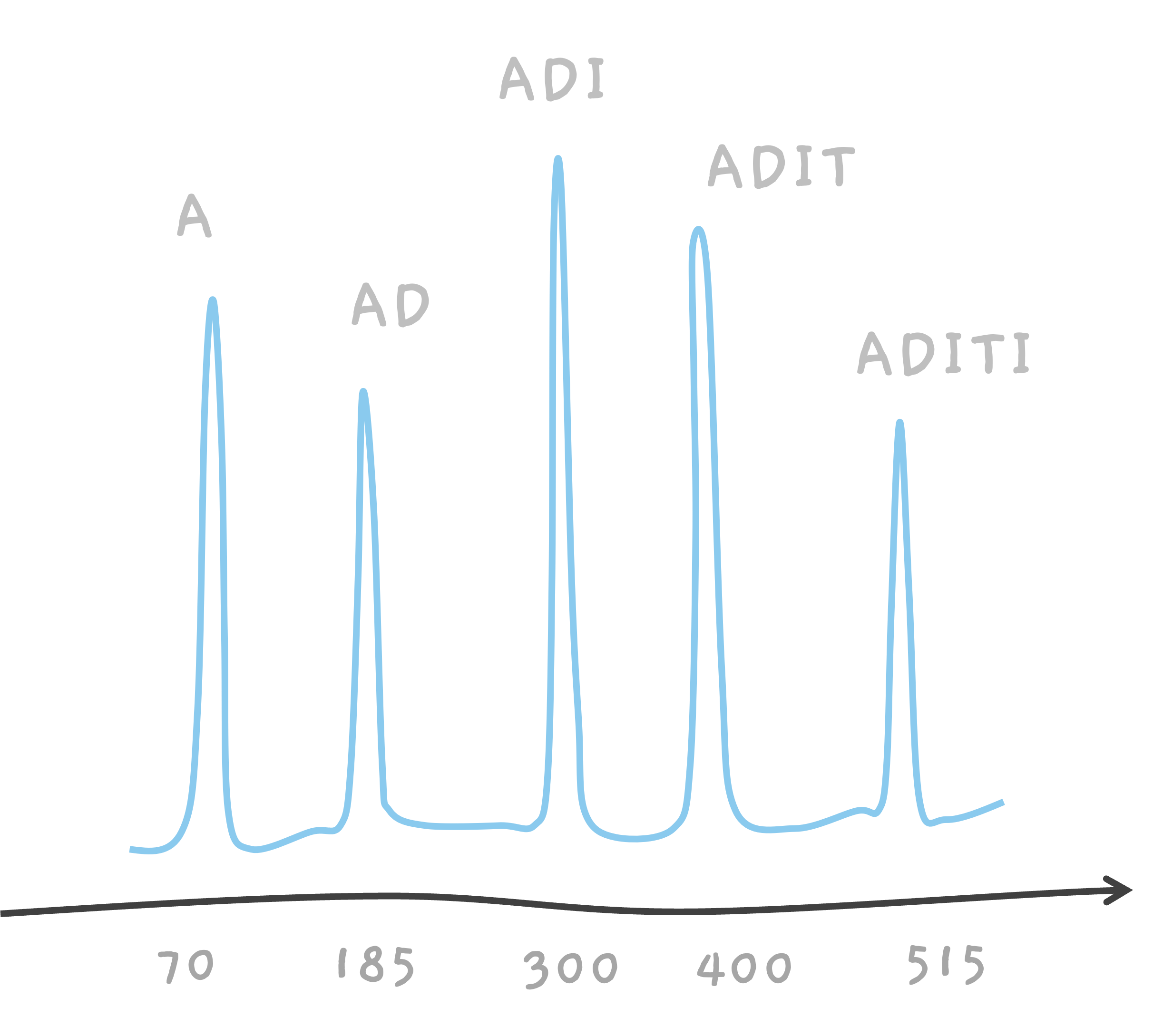

ADITI can break into A, AD, ADI and ADIT and so on.

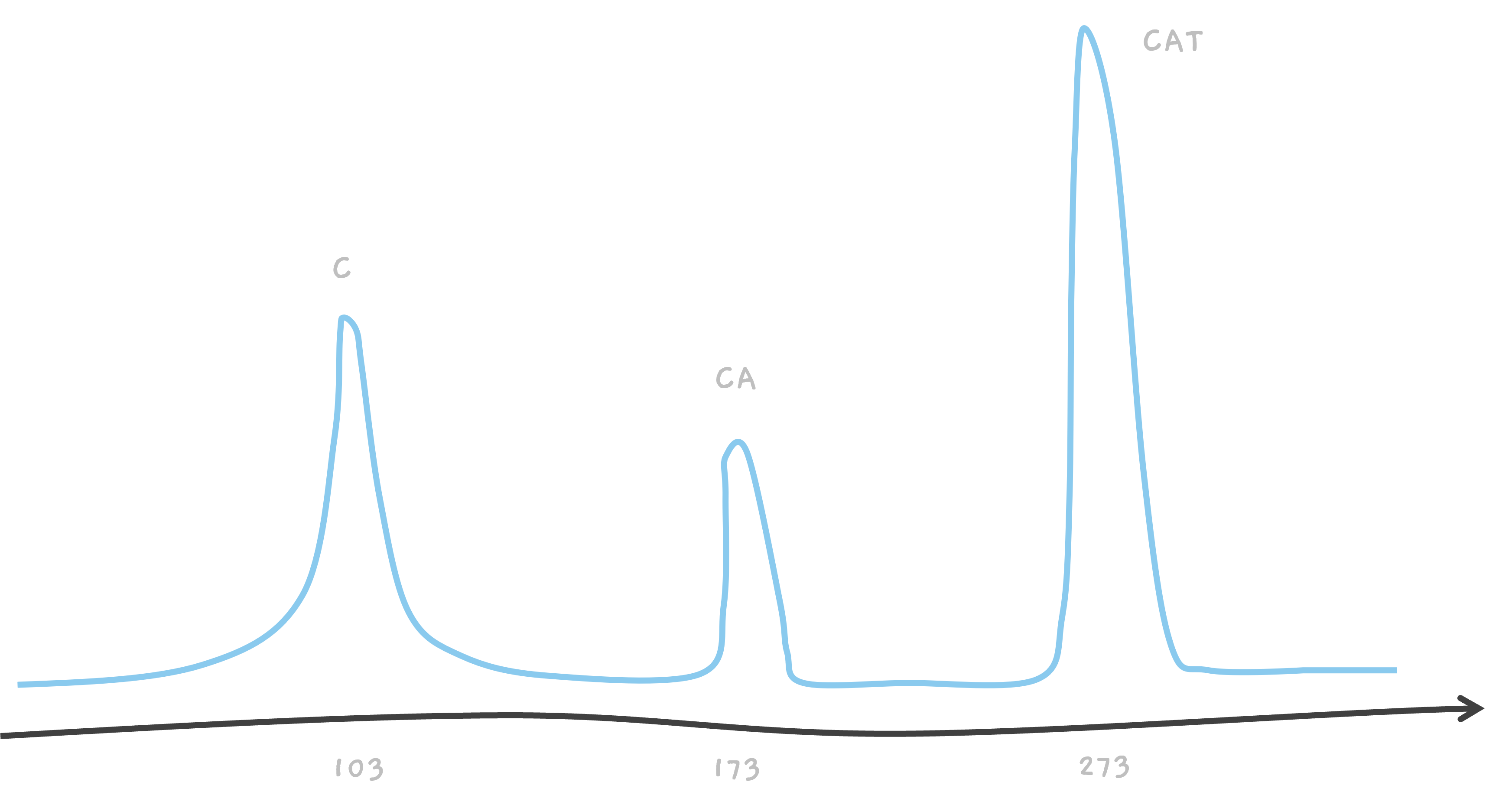

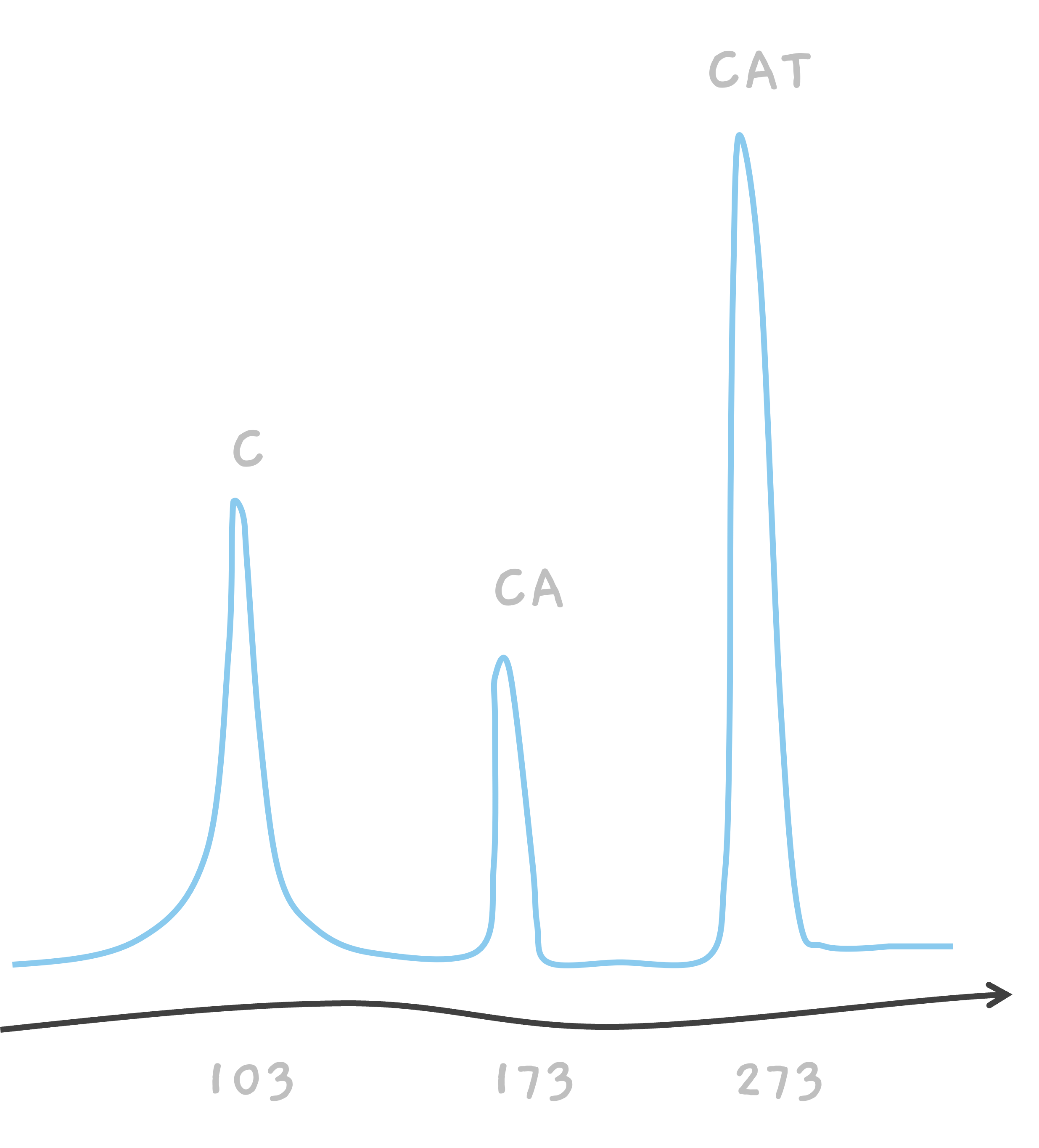

So, let's say, we've got our CAT peptide broken into C and CA parts. Now, when we feed these pieces into our trusty mass spectrometer to weigh, we should see two distinct signals 📈📉. One corresponds to the smaller C piece and another to the larger CA piece.

But hold on, what about the whole, unbroken CAT peptide? Well, it can still hang around in our sample, giving us a third signal 📊.

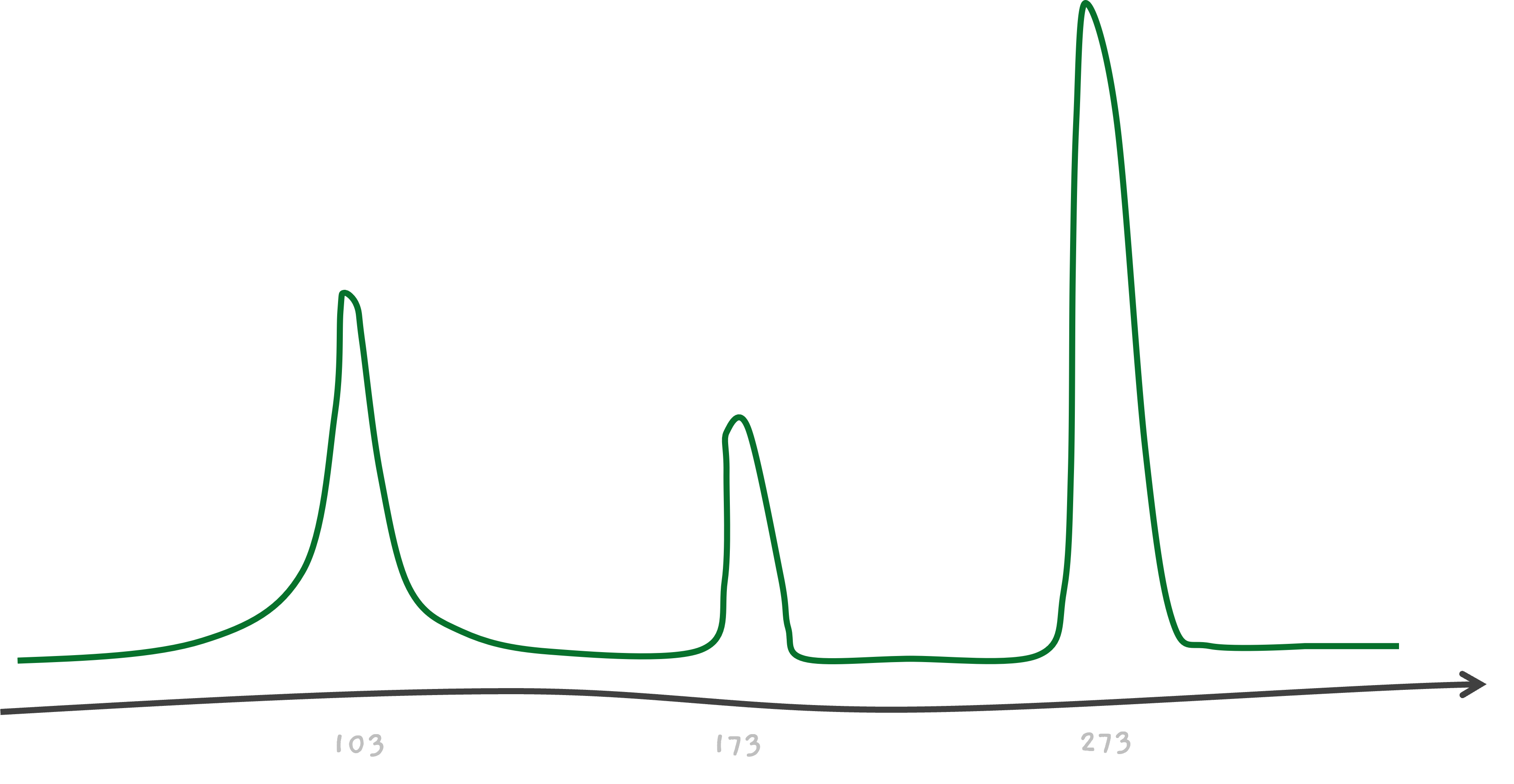

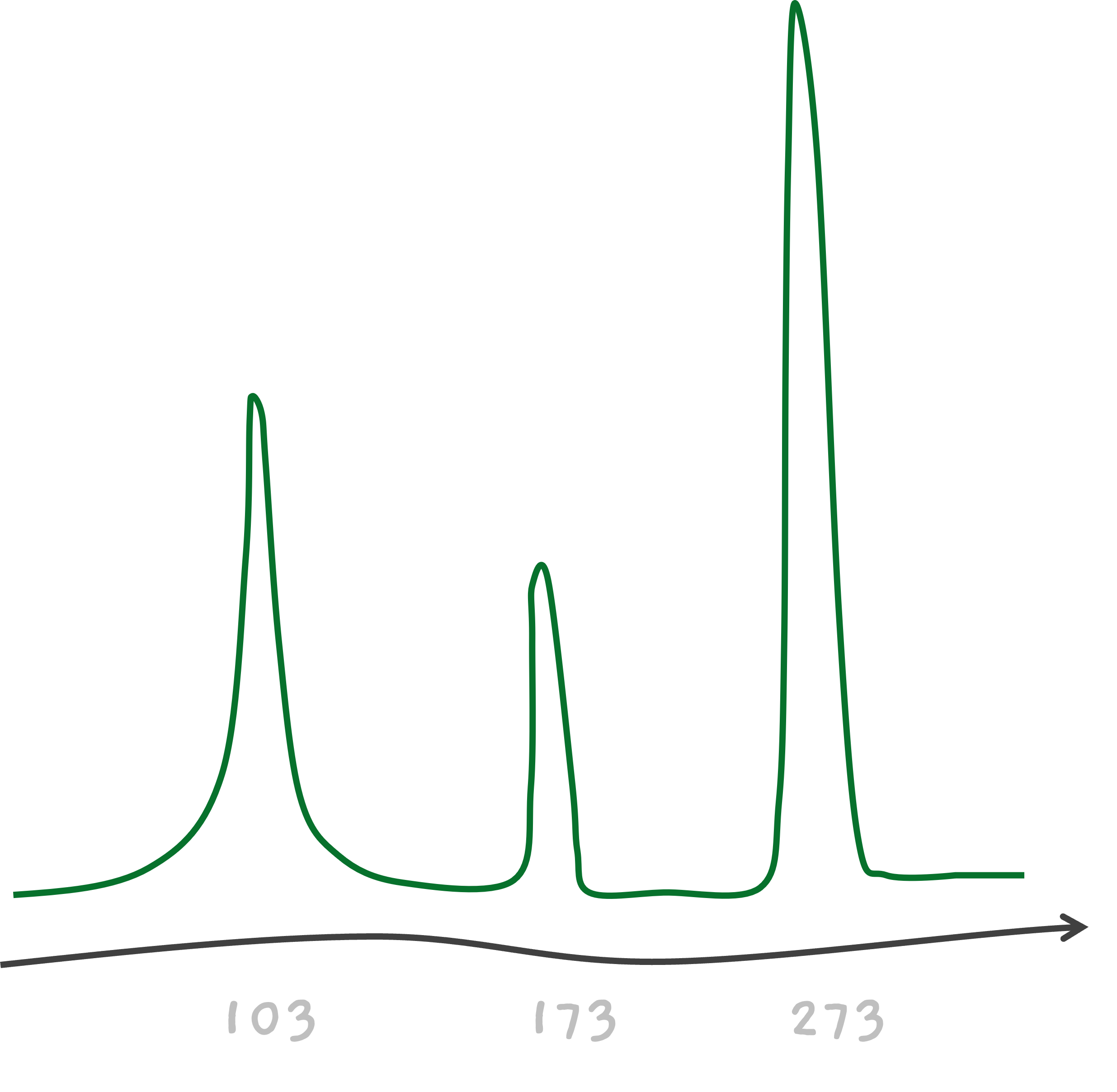

So, in the end, we've got three peaks on our mass spectrometer's readout, one for each of the C, CA, and the intact CAT.

For example, talking about CAT, we know that amino acid C weighs about 103 giving us a peak at 103. Similarly, we know that A weighs about 70, so the mass of CA must be 103 + 70 = 173, where we see the second peak. The mass of amino acid T is about 100, giving us another peak from CAT, at 103 + 70 + 100 = 273.

The same process happens with a peptide called ADITI. The peak at 300 is due to ADI, and as T is about 100, we get a peak at 400 corresponding to ADIT.

The values can be generated for any sequence. Here's a tool to try it out yourself. (use b ions checkbox only in the tool, this will be explained in detail later)

Fragment Ion Calculator - systemsbiology.net

But let's go back to CAT.. Let's say, you didn't know this was CAT peptide and we told you that this peptide had three amino acids. Can you figure out the amino acid sequence? Are you ready to perform De Novo Sequencing?

Let's do De Novo Sequencing

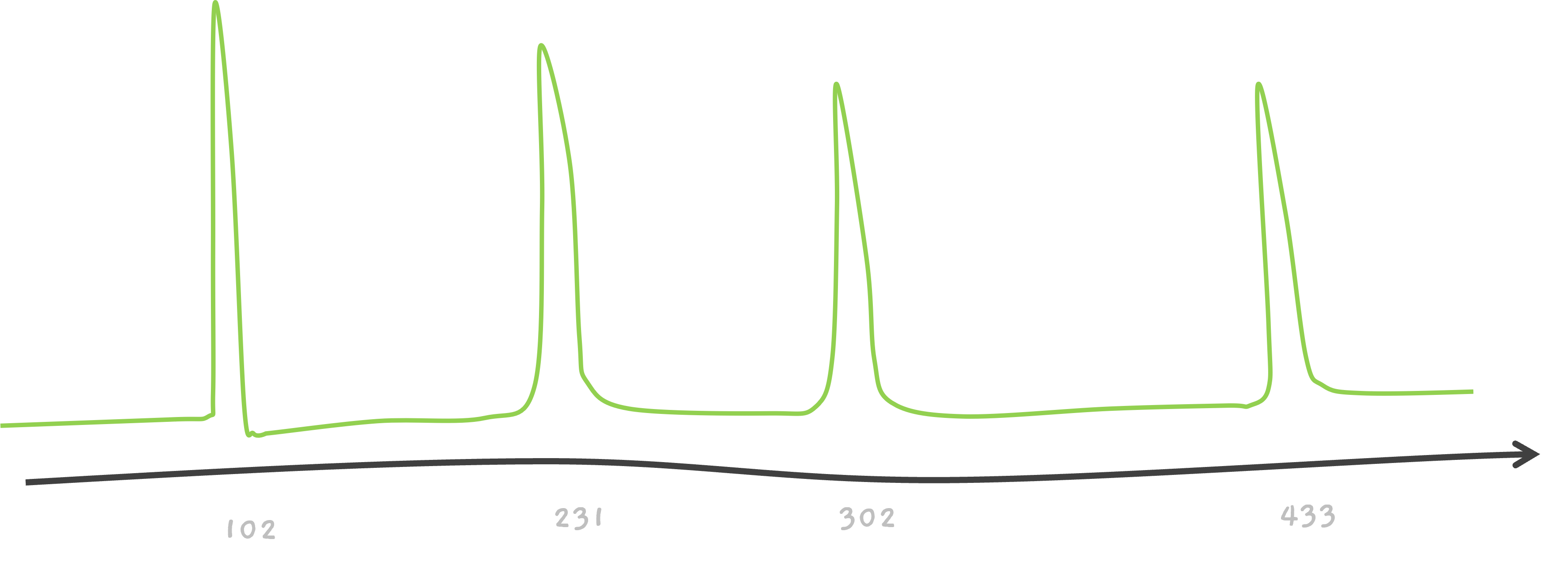

So, you have taken an unknown peptide, smashed it and then sent it into the mass spectrometer. The mass spectrometer has spit out a spectra with three humps. Time to figure out what was in the sample.

To begin, let's just call the unknown peptide X1 X2 X3.

The furthest peak must be from the largest mass, X1 X2 X3 itself, the unbroken peptide.

So, X1 X2 X3 weighs 273. This cannot directly tell us anything, as we know the masses of amino acids only. And yes, we are approximating here for simplicity.

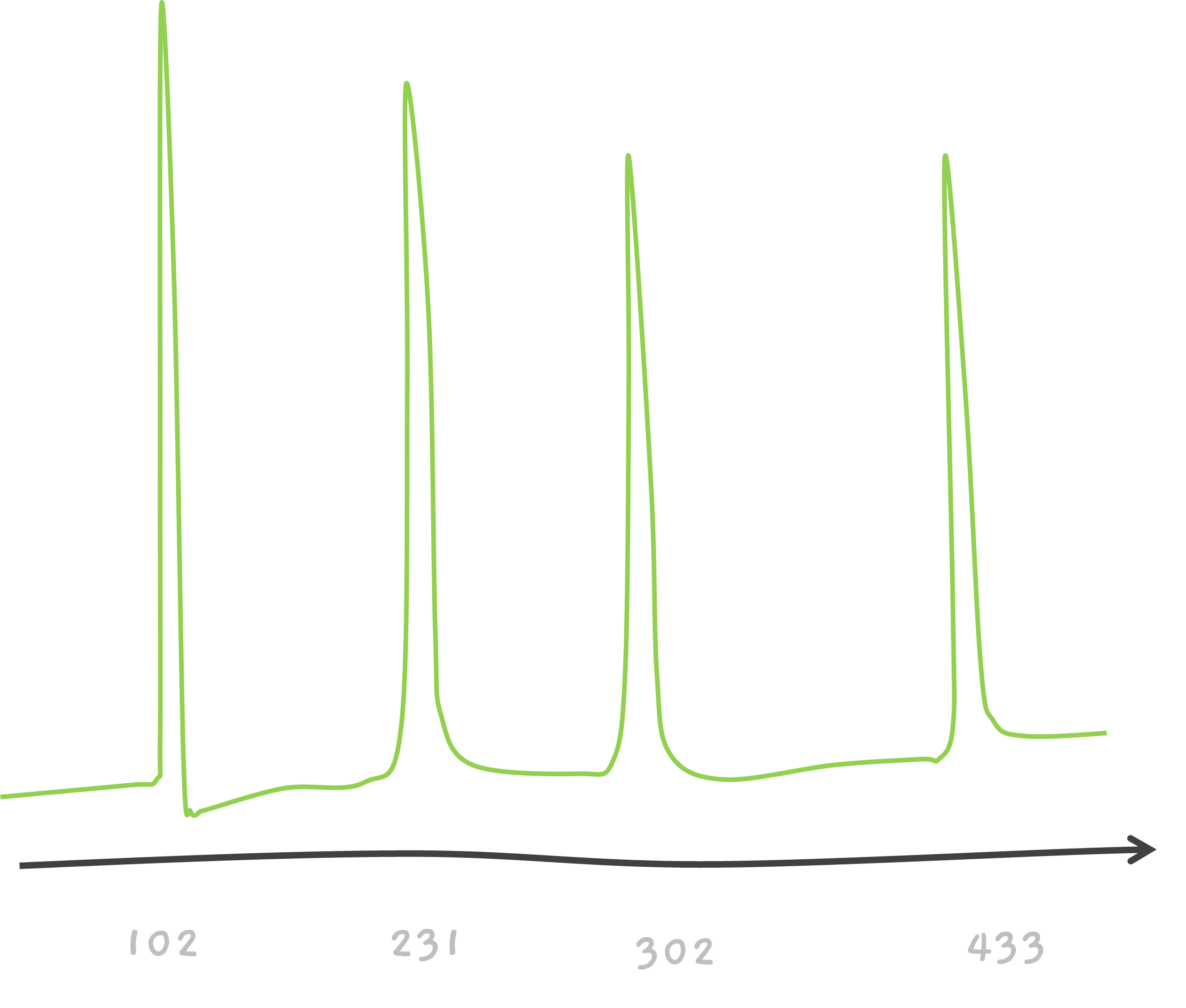

One can see that the peak for the smallest mass is 103 which should be the smallest fragment. So in our case, X1 is the smallest fragment and must have a mass of 103. This is a single amino acid. But which is it? This is when you go through the amino acid list. C is an amino acid with a mass of 103, so X1 must be C.

The next peak is at 173 and it must be from X1 X2. So, X1 X2 weighs 173.

This tells us that X2 must be an amino acid with a weight 70. Go through the amino acid list, there is an amino acid corresponding to 70, it's A, Alanine. So, X2 must be A. And finally, the peak at 273 must be from the whole peptide X1 X2 X3, so since X1 X2 is 173, X3 must be an amino acid with mass 100.. Which our list tells us, X3 must be T.

So.. we now know X1 X2 X3 is CAT. Congrats. That's your first de novo sequencing.

Now that you know, wanna try out another?

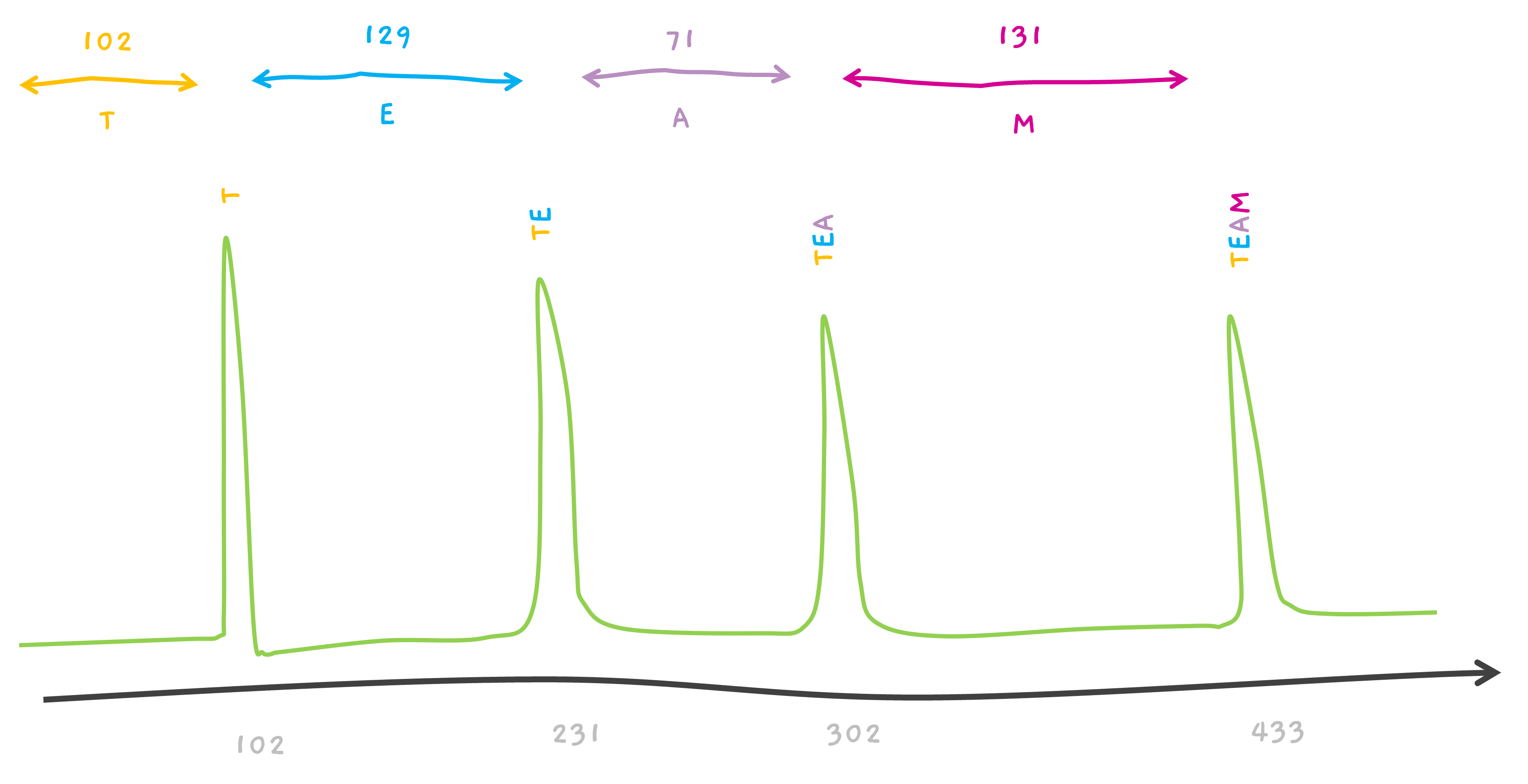

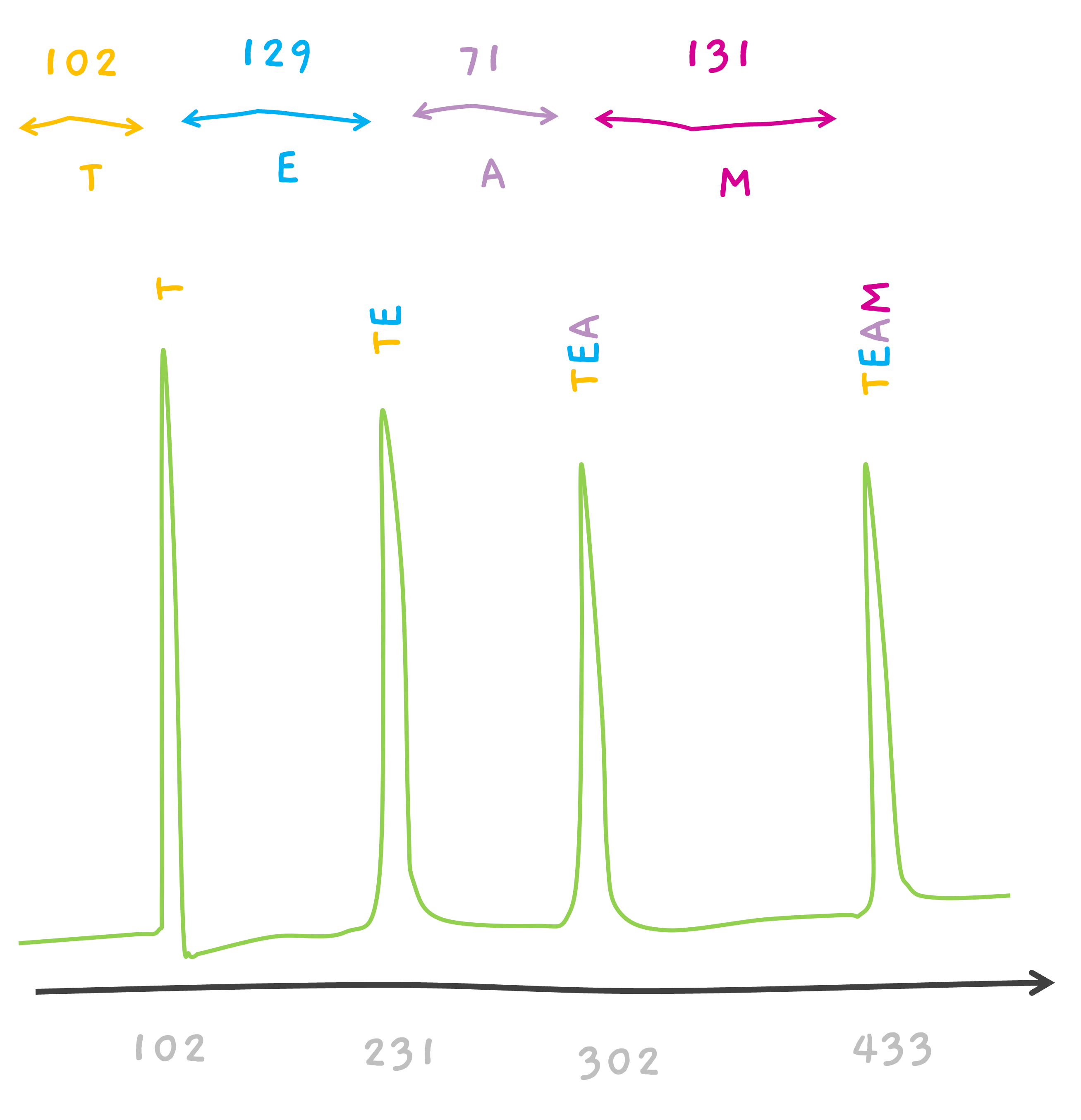

Here's some help, this one is 5 amino acids long peptides.

And the solution is…

TEAM.

CEAM? That's possible too.. If we consider 102 to be associated with C. This is a very simplified version. Because, isn't T, 101.04?

Yep, you caught us! 🎣 We did some rounding up, sort of like rounding up π to 3 (although not quite as dramatic!). However, it's important to note there's another simplification here that matters a lot. The ends of these peptides - imagine them like the caps on a tube of toothpaste 🦷 - can have some effects on the values we see in the spectra.

But hey, before we dive deeper into that, let's take a breather and try some fun puzzles 🧩. For now, let's simplify things and replace the peak curves with simple bars (kind of like a bar graph 📊), and maybe we'll skip over the intensities too. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to place the appropriate amino acids that match the bars. Ready? Set. Go! 🏁

Let's play. Here's some more examples to try out.

Simple isn't it? But Actually..

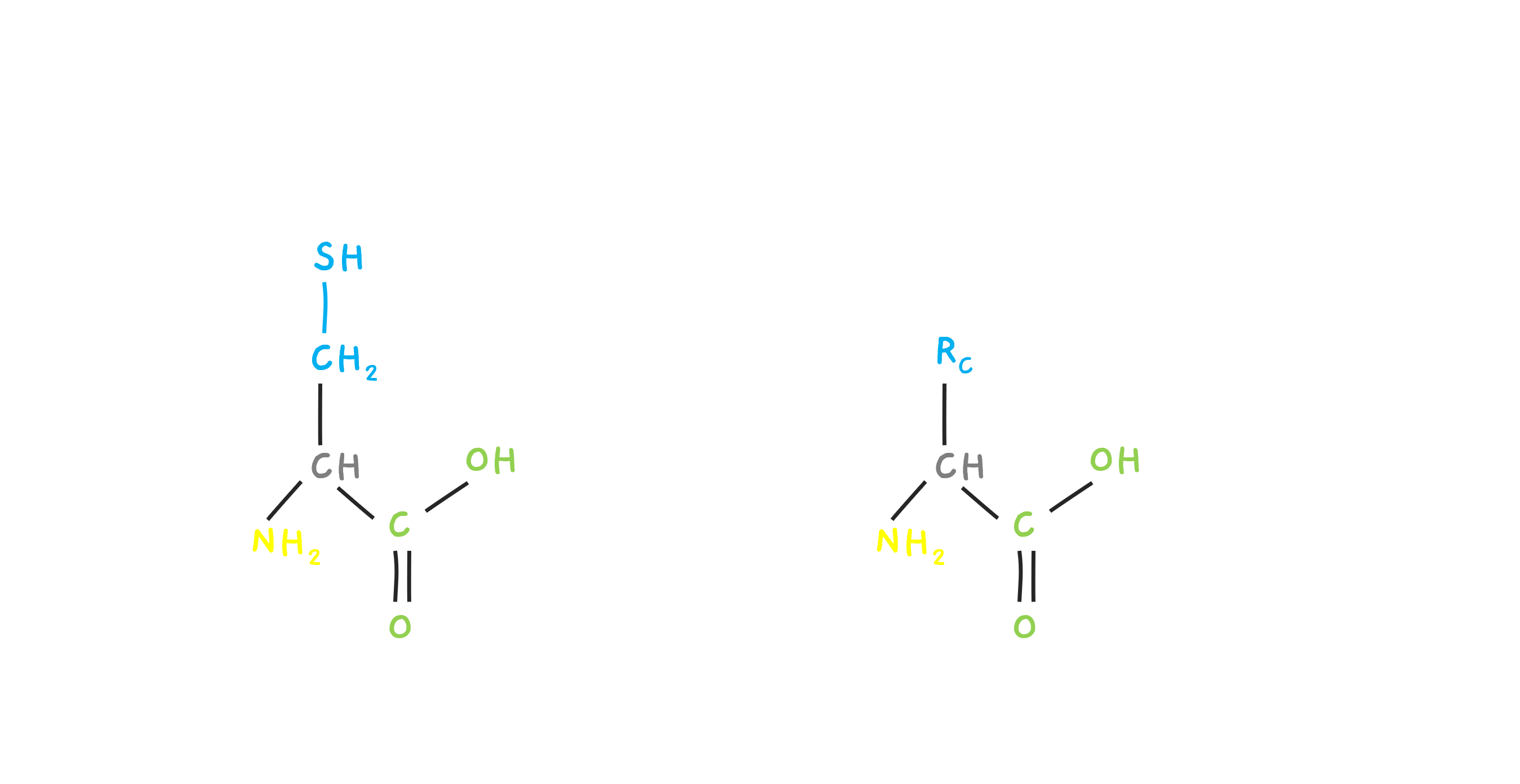

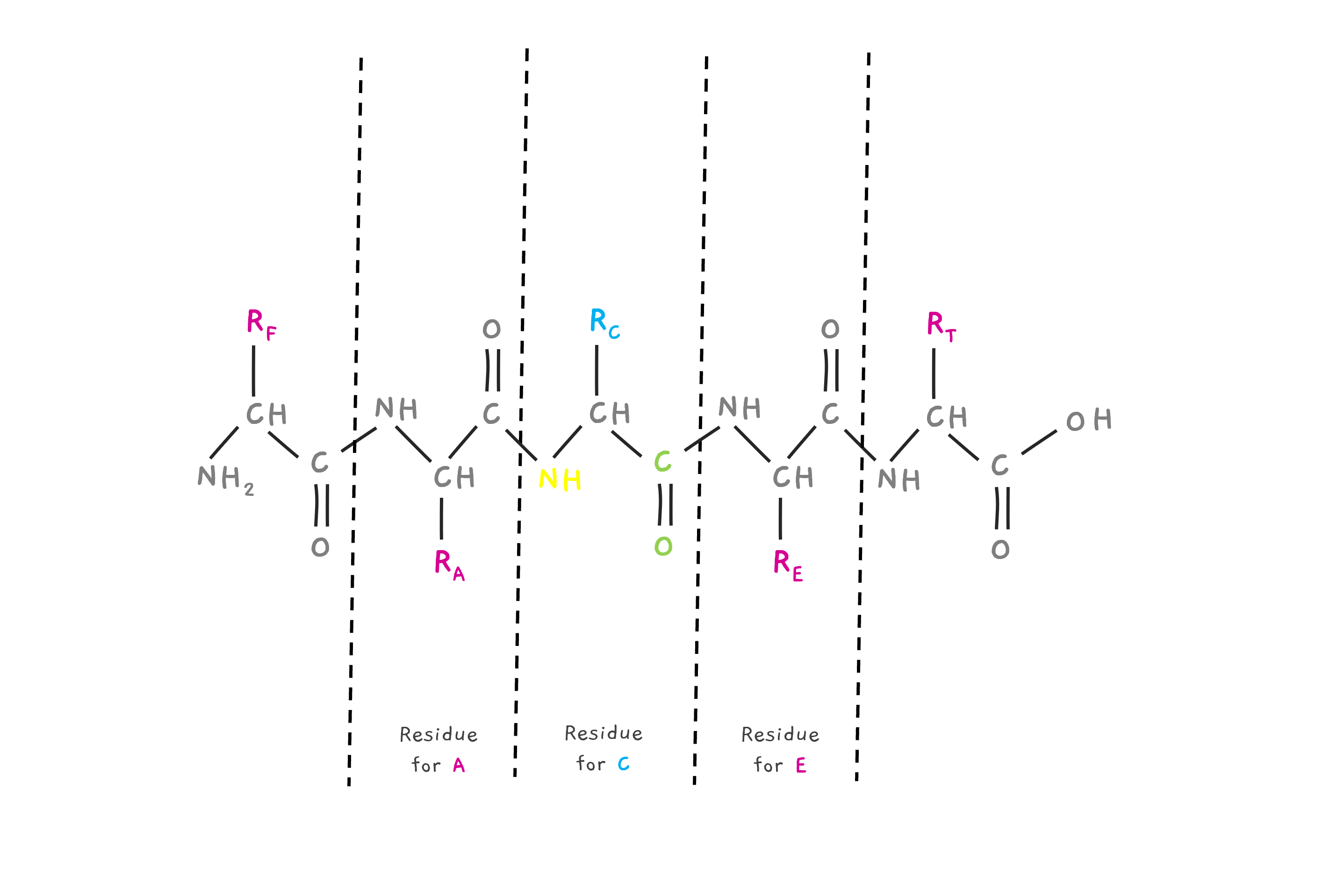

So.. things cannot be this simple right? Yep. There's more. What does it mean for the amino acid C (Cysteine) to have a mass of 103? Turns out, we are actually dealing with something called Residue mass. It will make sense in a moment. The amino acids have a particular structure. Let's look at Cysteine. There is a side chain called RC and for Cystine, it is CH2 - SH. This varies depending on the amino acid. There is an N-terminal (NH2) and a C terminal (COOH). This is when our amino acid is alone all by itself.

But, let's just say that it is joined by two new amino acids, A and E with side chains RA and RE forming a small peptide. Then, there is one H (Hydrogen) lost at the N terminal and an OH lost at the C terminal. Basically, a water molecule is lost. The residue mass of C is this mass, the whole amino acid mass, minus the water molecule that is lost. Similarly, we can see the residue of A and E. The residue contains the N and C end, but minus the H and OH.

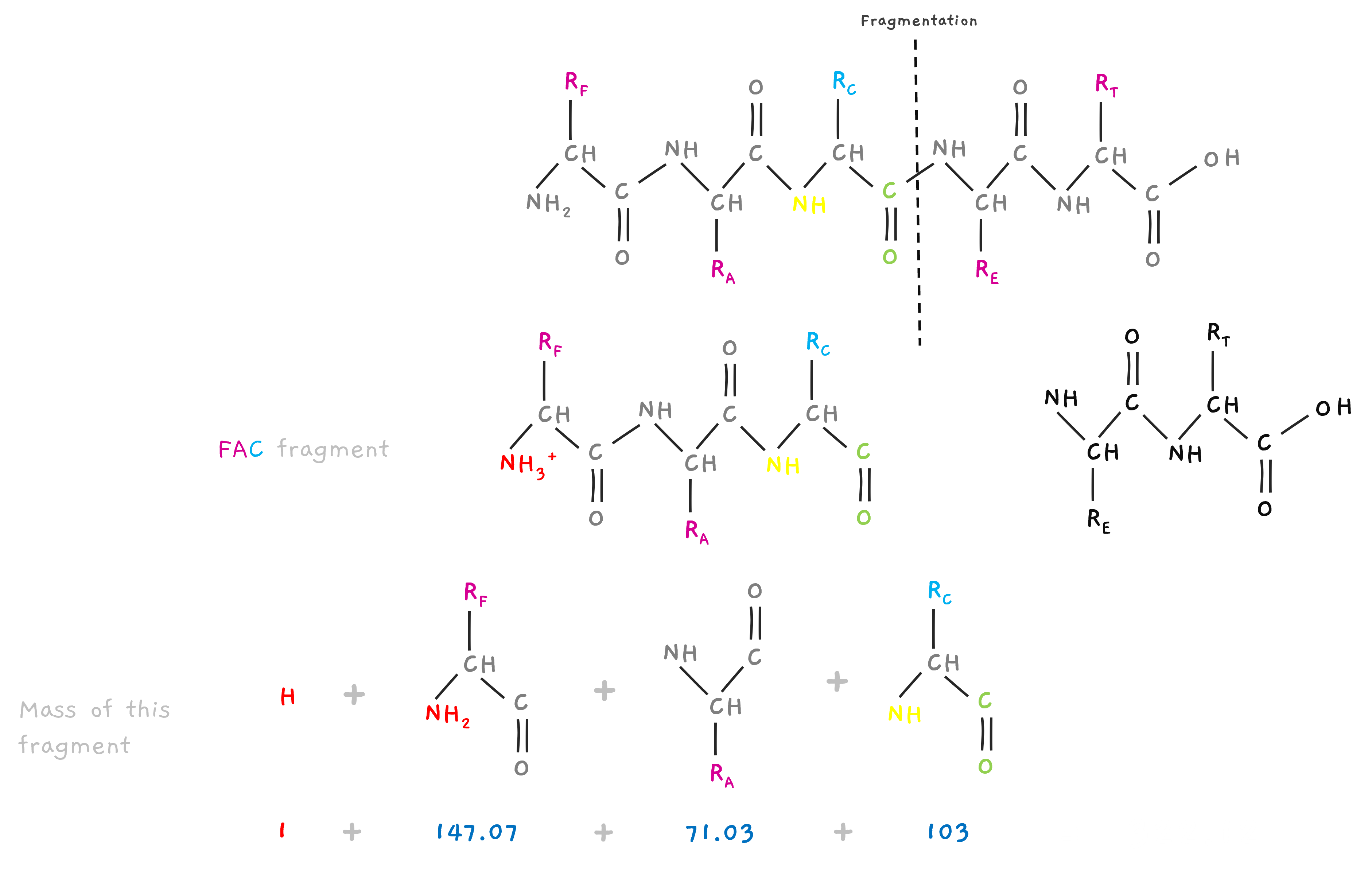

So, when fragmented by collision or other method before weighing them in the mass spectrometer. This collision often leads to a charge on the fragment of +1, adding a hydrogen to the N terminal. So.. Consider the peptide FAC above, If you want the mass of fragment FAC, you need to take the residual mass of F, A and C.. but also the extra hydrogen added to the N terminal of F.

So, the mass of the fragment is “shifted” by one unit.

Hope, why the spectra earlier was showing a peak at 102 instead of 101 for T, now makes sense. (and 231 for TE and 302 for TEA in the earlier section).

For more details on structures of other amino acids, you can look into

wikipedia.

This might seem like a co-incidence. But, we look for a circle when π pops up in various places right? Just check 3B1B :P So, why not dig a little deeper. And if we explore a little more, there are other seemingly unrelated math problems where you see this number show up.

So, What do you think is the average distance between any two points inside a unit square? Take a guess. :D

Move the slider to choose your answer... and also, the points A and B above are draggable. :)

Here is a slightly similar problem.

What do you think is the average distance between the center and any point 'inside' the unit square?

Take a guess. :D

PointB above is draggable. :)

It is about 0.38259785 ... To be exact, it is.

Yep. There's a P here too.

Let us start with a innocent looking problem. Picture a unit square, a perfect little 1x1 entity. Now, pick a point Q at random along the square's boundary. What do you think is the average distance between this chosen point Q and the very heart of our square, the center C?

The average distance is the typical or middle value obtained when you add up all the distances between any two points then divide by the number of distances you added together. It's a way of finding a 'common' or 'usual' distance in a group of different distances.

Surprisingly, the answer is approximately 0.5738967... a peculiar figure, isn't it? This number equals P/4 where P is known as Universal Parabolic Constant. The value is around 2.295587149... Hold on a second - a Parabolic Constant? But our question was about squares, wasn't it? Where does the parabola come in?